Deep Learning Rules of Thumb

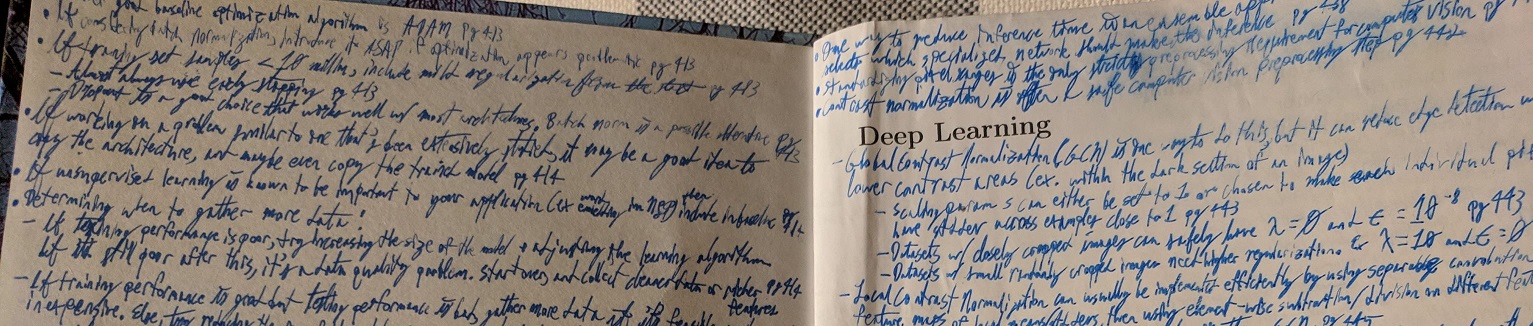

When I first learned about neural networks in grad school, I asked my professor if there were any rules of thumb for choosing architectures and hyperparameters. I half expected his reply of “well, kind of, but not really” – there are a lot more choices for neural networks than there are for other machine learning algorithms after all! I kept thinking about this when reading through Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaaron Courville’s Deep Learning book, and decided to compile a list of rules of thumbs listed throughout this book. As it turns out, there are a lot of them - especially since there are a lot of types of neural networks and tasks they can accomplish.

The funny thing is that a lot of these rules of thumb aren’t very heavily established – deep learning is still a relatively new active area of research, so a lot of ones listed below are just things that researchers may have recently discovered. Beyond that, there are a lot of areas in this book where the authors will either state (in more academic terms) “we don’t really know why this works, but we can see that it does” or “we know this isn’t the best way, but it is an active area of research and we don’t know any better ways at the moment”.

Below are the more practical notes that I have taken throughout reading Deep Learning. I included a TL:DR at the top to hit on the most important points, and I’d recommend skipping to Section 10: Practical Methodology for some of the more important parts if you don’t have a lot of time.

This isn’t a book review for Deep Learning, but I would personally recommend it if you’re looking to learn a more in depth understanding of the more established methodologies as well as the active areas of research (at the time of its publishing). Jeremy Howard of fast.ai (an excellent source for learning the practical side of deep learning) criticized this book due to focusing too much on the math and theory, but I found that it did a good job explaining the intuition behind concepts and practical methodologies in addition to all of the math formulas that I skipped over.

TL:DR

- Use transfer learning if possible. If not, and working on a problem that’s been studied extensively, start by copying the architecture.

- Network architecture should always be ultimately decided with experimentation and determined by the validation error.

- Deeper (more layers), thinner (smaller layers) networks are more difficult to optimize but tend to yield better generalization error.

- Always use early stopping.

- Two early stopping methods:

- Re-train the model again with new parameters on the entire dataset, and stop when hitting same number of training steps as the previous model at the early stopping point.

- Keep the parameters obtained at the early stop, continue training with all the data, and stop when the average training error falls below the training error at the previous early stopping point.

- Two early stopping methods:

- It’s probably a good idea to use dropout.

- Use a 0.8 keep probability on the input layers and 0.5 for hidden layers.

- Dropout may require larger networks that need to be trained with more iterations.

- ReLUs are the ideal activation function. They have flaws, so using leaky or noisy ReLUs could yield performance gains at the cost of having more parameters to tune..

- You need at least 5,000 observations per category for acceptable performance (>=10 million for human performance or better).

- Use k-folds cross validation instead of train/validation/test split if you have less than 100,000 observations.

- Use as large of a batch size as your GPU’s memory can handle.

- Try different batch sizes by increasing in powers of 2 starting with 32 (or 16 for really large models) and going up to 256.

- Stochastic gradient descent with momentum and a decaying learning rate is a good optimization algorithm to start with.

- Common values for the

hyperparameter for momentum are 0.5, 0.9, and 0.99. It can be adapted over time, starting with a small value and raising to larger values.

- Alternatively, use ADAM or RMSProp.

- Use asynchronous SGD if doing distributed deep learning.

- Common values for the

- The learning rate is the most important hyperpameter. If bound by time, focus on tuning it.

- The learning rate can be picked by monitoring learning curves that plot the objective function over time.

- The optimal learning rate is typically higher than the learning rate that yields the best performance after the first ~100 iterations, but not so high that it causes instability..

- For computer vision:

- Use data augmentation as long as flipping the images doesn’t fundamentally change the image. Contrast normalization is another safe pre-processing step.

- Batch normalization, pooling, and padding are common tools to use with convolutional neural networks. Batch normalization may make dropout redundant.

- For natural language processing:

- Long short term memory (LSTM) networks typically outperform other neural networks.

- Pre-trained word embeddings (ex. word2vec, word2glove, etc.) are powerful.

- Random search typically converges to good hyperparameters faster than grid search.

- Debugging strategies:

- Visualize the model in action: Look at samples of images and what the model detects. This helps determine if the quantitative performance numbers are reasonable.

- Visualize the worst mistakes: This can reveal problems with pre-processing or labeling.

- Fit a tiny dataset when the training error is high: This helps determine genuine underfitting vs. software defects .

- Monitor a histogram of activations and gradients: Do this for about one epoch. This tells us if the units saturate and how often. The gradient should be about 1% of the parameter.

Full comprehensive notes

I) Applied Math and Machine Learning Basics

1. Introduction

- At least 5,000 observations per category are typically required for acceptable performance. (pg. 20)

- More than 10,000,000 observations per category are typically required for human performance or better. (pg. 20)

4. Numerical Computation

- In deep learning we typically settle for local minima rather than the global minima because of complexity and non-convex problems. (pg. 81)

5. Machine Learning Basics

- If your model is at optimal capacity and there is still a gap between training and testing error, gather more data. (pg. 113)

- 20% of a training set is typically used for the validation set. (pg. 118)

- Use k-folds cross validation instead of a train/test split if the dataset has less than 100,000 observations. (pg. 119)

- When using mean squared error (MSE), increasing capacity lowers bias but raises variance. (pg. 126)

- Bayesian methods typically generalize much better when limited training data is available, but they typically suffer from high computational cost when the number of training examples is large. (pg. 133)

- The most common cost function is the negative log-likelihood. As a result, minimizing the cost function causes maximum likelihood estimation. (pg. 150)

II) Deep Networks: Modern Practices

6. Deep Feedforward Networks

- Rectified linear units (ReLU) are an excellent default choice for an activation function for feed forward neural networks. (pg. 186)

- They are based on the principle that models are easier to optimize if their behavior is closer to linear. (pg. 188)

- Sigmoidal activations should be used when ReLUs aren’t possible. Ex. RNNs, many probabilistic models, and some autoencoders. (pg. 190)

- Cross entropy is preferred over mean squared error (MSE) or mean absolute error (MAE) in gradient based optimization because of vanishing gradients. (pg. 178)

- ReLU advantages: Reduced likelihood of vanishing gradients, sparsity, and reduced computation. (pg. 187)

- ReLU disadvantages: Dying ReLU (leaky or noisy ReLUs avoid this, but introduce additional parameters that need to be tuned). (pg. 187)

- Large gradients help with learning faster, but arbitrarily large gradients result in instability. (pg. 183)

- Network architectures should ultimately be found via experimentation guided by monitoring the validation set error. (pg. 192)

- Deeper models reduce the number of units required to represent the function and reduce generalization error. (pg. 193)

- Intuitively, models with deeper layers are preferred because we are learning a series of functions on the overall function. (pg. 195)

7. Regularization for Deep Learning

- It’s optimal to use different regularization coefficients at each layer, but use the same weight decay at all layers. (pg. 223)

- Use early stopping. It’s an efficient hyperparameter to tune, and it will prevent unnecessary computations. (pg. 241)

- Two methods for early stopping:

- Re-train the model again with new parameters on the entire dataset, and stop when hitting same number of training steps as the previous model at the early stopping point. (pg. 241)

- Keep the parameters obtained at the early stop, continue training with all the data, and stop when the average training error falls below the training error at the previous early stopping point. (pg. 242)

- Two methods for early stopping:

- Model averaging (bagging, boosting, etc.) almost always increase predictive performance at the cost of computational power. (pg. 249)

- Averaging tends to work well because different models will usually not make all the same errors on the test set. (pg. 249)

- Dropout is effectively a way of bagging by creating sub-networks. (pg. 251)

- Dropout works better on wide layers because it reduces the chances of removing all of the paths from the input to the output. (pg. 252)

- Common dropout probabilities for keeping a node are 0.8 for the input layer and 0.5 for the hidden layers. (pg. 253)

- Models with dropout need to be larger and need to be trained with more iterations. (pg. 258)

- If a dataset is large enough, dropout likely won’t help too much. (pg. 258)

- Additionally, dropout is not very effective with a very limited number of training samples (ex. <5,000). (pg. 258)

- Batch normalization also adds noise which has a regularizing effect and may make dropout unnecessary. (pg. 261)

8. Optimization for Training Deep Models

- Mini-batch size (i.e. batch size): Larger batch sizes offers better gradients, but are typically limited by memory. (pg. 272)

- I.e. make your batch size as high as your memory can handle. (pg. 272)

- With GPUs, increase the batch size by a power of 2, from 32 to 256. Try starting with a batch size of 16 for larger models. (pg. 272)

- Small batch sizes can have a regularizing effect due to noise, but at the cost of adding to the total run time. These cases require smaller learning rates for increase stability. (pg. 272)

- Deep learning models have multiple local minima, but it’s ok because they all have the same cost. The main problem is if the cost at the local minima is much greater than the cost at the global minima. (pg. 277)

- You can test for problems from local minima by plotting the norm of the gradient and seeing if it shrinks to an extremely small value over time. (pg. 278)

- Saddle points are much more common than local minima in high dimensional non-convex functions. (pg. 278)

- Gradient descent is relatively robust to saddle points. (pg. 279)

- Gradient clipping is used to stop exploding gradients. This is a common problem for recurrent neural networks (RNNs). (pg. 281)

- Pick learning rate by monitoring learning curves that plot the objective function over time. (pg. 287)

- Optimal learning rate is higher than the learning rate that yields the best performance after the first ~100 iterations. (pg. 287)

- Monitor the first few iterations and go higher than the best performing learning rate while avoiding instability. (pg. 287)

- It doesn’t seem to matter much if initial variables are randomly selected from a Gaussian or uniform distribution. (pg. 293)

- However, the scale does. Larger initial weights help avoid redundant units, but initial weights that are too large have a detrimental effect. (pg. 294)

- Weight initialization can be treated as hyperparameter - specifically the initial scale and if they are sparse or dense. (pg. 296)

- Look at the range or standard deviation of activations or gradients on one minibatch for picking the scale. (pg. 296)

- There is no one clear optimization algorithm that outperforms the others - it primarily depends on user familiarity of hyperparameter tuning. (pg. 302)

- Stochastic gradient descent (SGD), SGD with momentum, RMSProp, RMSprop with momentum, AdaDelta, and Adam are all popular choices. (pg. 302)

- RMSProp is an improved version of AdaGrad (pg. 299) and is currently one of the go-to optimization methods for deep learning practitioners. (pg. 301)

- Note: RMSProp may have high bias early in training. (pg. 302)

- Common values for the

hyperparameter for momentum are 0.5, 0.9, and 0.99. (pg. 290)

- This hyperparameter can be adapted over time, starting with a small value and raising to larger values. (pg. 290)

- Adam is generally regarded as being fairly robust to the choice of hyperparameters. (pg. 302)

- However, the learning rate may need to be changed from the suggested default. (pg. 302)

- RMSProp is an improved version of AdaGrad (pg. 299) and is currently one of the go-to optimization methods for deep learning practitioners. (pg. 301)

- Stochastic gradient descent (SGD), SGD with momentum, RMSProp, RMSprop with momentum, AdaDelta, and Adam are all popular choices. (pg. 302)

- Apply batch normalization to the transformed values rather than the input. Omit the bias term if including the

learnable parameter. (pg. 312)

- Apply range normalization in and at every spatial location for convolutional neural networks (CNNs). (pg. 312)

- Networks that are more thin and deep are more difficult to train, but they have better generalization error. (pg. 317)

- It is more important to choose a model family that is easy to optimize than a powerful optimization algorithm. (pg. 317)

9. Convolutional Networks

- Pooling is essential for handling inputs of varying size. (pg. 338)

- Zero padding allows us to control the kernel width and output size independently to stop shrinkage, which would be a limiting factor. (pg. 338)

- The optimal amount of zero padding for test set accuracy usually lies between:

- “Valid convolutions” where no zero padding is used, the kernel is always entirely in the image, but output shrinks every layer. (pg. 338)

- “Same convolutions” where enough zero padding is used to keep the size of the output equal to the size of the input. (pg. 338)

- One potential way to evaluate convolutional architectures is to use randomized weights and only train the last layer. (pg. 352)

10. Sequence Modeling: Recurrent and Recursive Nets

- Bidirectional RNNs have been extremely successful in handwriting recognition, speech recognition, and bioinformatics. (pg. 383)

- Compared to CNNs, RNNs applied to images are typically more expensive but allow for long-range lateral interactions between features in the same feature map. (pg. 384)

- Whenever a RNN has to represent long-term dependencies, the long term interactions gradients have an exponentially smaller magnitude than the gradients of the short term interactions. (pg. 392)

- The technologies used to set the weights in echo state networks could be used to initialize weights in a fully trainable RNN – an initial spectral radius of 1.2 and sparse initialization perform well. (pg. 395)

- The most effective sequence models in practice are gated RNNs – including long short-term memory units (LSTMs) and gated recurrent units (pg. 397)

- LSTMs learn long-term dependencies more easily than simple RNNs. (pg. 400)

- Adding a bias of 1 to the forget gate makes the LSTM as strong as gated recurrent network (GRN) variants. (pg. 401)

- Using SGD on LSTMs typically takes care of using second-order optimization methods to prevent second derivatives vanishing with the first derivatives. (pg. 401)

- It is often much easier to design a model that is easier to optimize than it is to design a more powerful algorithm. (pg. 401)

- Regularization parameters encourage “information flow” and prevents vanishing gradients. However, gradient clipping is needed for RNNs to also prevent gradient explosion (which would prevent learning from succeeding). (pg. 404)

- However, this is not very effective for LSTMs with a lot of data, e.g. language modeling. (pg. 404)

11. Practical Methodology

- It can be useful to have a model refuse to make a decision if it is not confident, but there is a tradeoff. (pg. 412)

- Coverage is the fraction of samples for which the machine learning sample is able to produce a response for, and it is a tradeoff with accuracy. (pg. 412)

- ReLUs and their variants are the ideal activation functions for baseline models. (pg. 413)

- A good choice for a baseline optimization algorithm is SGD with momentum and a decaying learning rate. (pg. 413)

- Decay schemes include:

- Linear decay until fixed minimum learning rate (pg. 413)

- Exponential decay (pg. 413)

- Decreasing by a factor of 2 to 10 each time the validation error plateaus (pg. 413)

- Decay schemes include:

- Another good baseline optimization algorithm is ADAM. (pg. 413)

- If considering batch normalization, introduce it ASAP if optimization appears problematic. (pg. 413)

- If there are <10 million samples in the training set, include mild regularization from the start. (pg. 413)

- Almost always use early stopping. (pg. 413)

- Dropout is a good choice that works well with most architectures. Batch normalization is a possible alternative. (pg. 413)

- If working on a problem similar to one that’s been extensively studied, it may be a good idea to copy that architecture, and maybe even copy the trained model. (pg. 414)

- If unsupervised learning is known to be important to your application (e.g. word embedding in NLP) then include it in the baseline. (pg. 414)

- Determining when to gather more data:

- If training performance is poor, try increasing the size of the model and adjusting the learning algorithm. (pg. 414)

- If it is still poor after this, it is a data quality problem. Start over and collect cleaner data or more rich features. (pg. 414)

- If training performance is good but testing performance is bad, gather more data if it is feasible and inexpensive. Else, try reducing the size of the model or improve regularization. If these don’t help, then you need more data. (pg. 415)

- If you can’t gather more data, the only remaining alternative is to try to improve the learning algorithm. (pg. 415)

- Use learning curves on a logarithmic scale to determine how much more data to gather. (pg. 415)

- If training performance is poor, try increasing the size of the model and adjusting the learning algorithm. (pg. 414)

- The learning rate is the most important hyperparameter because it controls the effective model capacity in a more complicated way than other hyperparameters. If bound by time, tune this one. (pg. 417)

- Tuning other hyperpameters requires monitoring both training and testing error for determining if the model is over/under fitting. (pg. 417)

- If training error is higher than the target error, increase capacity. If not using regularization and are confident that the optimization algorithm is working properly, add more layers/hidden units. (pg. 417)

- If testing error is higher than the target error, regularize. Best performance is usually found on large models that have been regularized well. (pg. 418)

- Tuning other hyperpameters requires monitoring both training and testing error for determining if the model is over/under fitting. (pg. 417)

- As long as your training error is low, you can always decrease generalization error by collecting more training data. (pg. 418)

- Grid search: Commonly selected when tuning less than four hyperpameters. (pg. 420)

- It’s typically best to select values on a logarithmic scale and use it repeatedly to narrow down values. (pg. 421)

- Computational cost is exponential with the number of hyperparameters, so even parallelization may not help out adequately. (pg. 422)

- Random search: It is often simpler to use and converges to good hyperparameters much quicker than grid search. (pg. 422)

- Random search can be exponentially more efficient than grid search when there are several hyperparameters that don’t strongly affect the performance measure. (pg. 422)

- We may want to run repeated versions of it to refine the search based off of previous results. (pg. 422)

- Random search is faster than grid search because it doesn’t waste experimental runs. (pg. 422)

- Model based hyperparameter tuning isn’t universally recommended because it rarely outperforms humans and can catastrophically fail. (pg. 423)

- Debugging strategies:

- Visualize the model in action. I.e. look at samples of images and what the model detects. This helps determine if the quantitative performance numbers are reasonable. (pg. 425)

- Visualize the worst mistakes. This can reveal problems with pre-processing or labeling. (pg. 425)

- Fit a tiny dataset when the training error is high. This helps determine genuine underfitting vs. software defects. (pg. 426)

- Monitor a histogram of activations and gradients: Do this for about one epoch. This tells us if the units saturate and how often. (pg. 427)

- Compare magnitude of gradients to parameters. The gradient should be about ~1% of the parameter. (pg. 427)

- Sparse data (e.g. NLP) have some parameters that are rarely updated. Keep this in mind. (pg. 427)

- Compare magnitude of gradients to parameters. The gradient should be about ~1% of the parameter. (pg. 427)

12. Applications

- When using a distributed system, use asynchronous SGD. The average improvement of each step is lower, but the increased rate of production of steps causes this to be faster overall. (pg. 435)

- Cascade classifiers is an efficient approach for object detection. One classifier with high recall

another with high precision. E.g. locate street sign

transcribe address. (pg. 437)

- One way to reduce inference time in an ensemble approach is to train a “gater” that selects which specialized network should make the inference. (pg. 438)

- Standardizing pixel ranges is the only strict preprocessing required for computer vision. (pg. 441)

- Contrast normalization is often a safe computer vision preprocessing step. (pg. 442)

- Global contrast normalization (GCN) is one way to do this, but it can reduce edge detection within lower contrast areas (e.g. within the dark section of an image). (pg. 442 & 444)

- Scaling parameters can either be set to 1 or chosen to make each individual pixel have a standard deviation across examples close to 1. (pg. 443)

- Datasets with closely cropped images can safely have

and

. (pg. 443)

- Datasets with small randomly cropped images need higher regularization. E.g.

and

. (pg. 443)

- Local contrast normalization can usually be implemented effectively by using separable convolution to compute feature maps of local means/standard deviations, then using element-wise subtraction/division on different feature maps. (pg. 444)

- This typically highlight edges more than global contrast normalization. (pg. 445)

- Global contrast normalization (GCN) is one way to do this, but it can reduce edge detection within lower contrast areas (e.g. within the dark section of an image). (pg. 442 & 444)

- In NLP, hierarchical softmax tends to give worse test results than sampling-based methods in practice. (pg. 457)

III) Deep Learning Research

13. Linear Factor Models

- Linear factor models can be extended into autoencoders and deep probabilistic models that do the same tasks but are much more flexible and powerful. (pg. 491)

14. Autoencoders

- Sparse autoencoders are good for learning features for other tasks such as classification. (pg. 496)

- Autoencoders are useful for learning which latent variables explain the input. They can also learn useful features. (pg. 498)

- While many autoencoders have one encoder/decoder layer, they can take the same advantages of depth as feedforward networks. (pg. 499)

- This especially applies when enforcing constraints such as sparsity. (pg. 500)

- Depth exponentially reduces computational cost and the amount of training data for representing some functions. (pg. 500)

- A common strategy for training a deep autoencoder is to greedily pre-train the deep architecture by training a stack of shallow autoencoders. (pg. 500)

15. Representation Learning

- In machine learning, a good representation is one that makes a subsequent learning task easier. (pg. 517)

- Ex. supervised feed forward networks: each layer learns better representations for the classifier from the last layer. (pg. 518)

- Greedy layer-wise unsupervised training can help with classification test error, but not many other tasks. (pg. 520)

- It is not useful with image classification, but it is very important in NLP (e.g. word embedding) because of a poor initial representation. (pg. 523)

- From a regularizer perspective, it’s most effective when the number of labeled examples are very small or the number of unlabeled examples are very large. (pg. 523)

- It’s likely to be most useful when the function to be learned is extremely complicated. (pg. 523)

- Use the validation error from the supervised phase to select the hyperparameters of the pretraining phase. (pg. 526)

- Unsupervised pretraining has mostly been abandoned except for use in NLP (e.g. word embedding). (pg. 526)

- Transfer learning, multitask learning, and domain adaptation can be achieved with representation learning when there are features useful for different tasks/settings corresponding to underlining factors appearing in multiple settings. (pg. 527)

- Distributed representations can have a statistical advantage to non-distributed representations when an already complicated structure can be compactly represented using a smaller number of parameters. (pg. 540)

- Some traditional non-distributed algorithms generalize because of the smoothness assumption, but this suffers from the curse of dimensionality. (pg. 540)

16. Structured Probabilistic Models for Deep Learning

- Structured probabilistic models provide a framework for modeling only direct interactions between random intervals, which allow the models to have significantly fewer parameters. Because of this, they can be estimated reliably from less data and having a reduced computational cost for storing the model, performing inference, and drawing samples. (pg. 553)

- Many generative models in deep learning have either no latent variables or only use one layer of latent variables. These use deep computational graphs to define the conditional distributions within a model. (pg. 575)

- This is in contrast to most deep learning applications where there tend to be more latent variables than observed variables. These are learned for nonlinear interactions. (pg. 575)

- Latent variables in deep learning are unconstrained but are difficult to interpret outside of rough characterization via visualization. (pg. 575)

- Loopy belief propagation is almost never used in deep learning because most deep learning models are designed to make Gibbs sampling or variational inference algorithms efficient. (pg. 576)

17. Monte Carlo Methods

- Monte Carlo Markov Chains (MCMC) can be computationally expensive to use because of the time required to “burn in” the equilibrium distribution and to keep every n sample in order to assure your samples aren’t correlated. (pg. 589)

- When sampling from MCMC in deep learning, it is common to run a number of parallel markov chains that is equal to the number of samples in a minibatch, and then sample from these. 100 is a common number to use. (pg. 589)

- Markov chains will reach equilibrium, but we don’t know how long until it does or when it does. We can test if it has mixed with heuristics like manually inspecting samples or measuring correlation between successive samples. (pg. 589)

- While the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is often used with Markov chains in other disciplines, Gibbs sampling is the de-facto method for deep learning. (pg. 590)

19. Approximate Inference

- Maximum a posteriori (MAP) inference is commonly used with a feature extractor and learning mechanism, primarily for sparse coding models. (pg. 628)

20. Deep Generative Models

- Variants of the Boltzmann machine surpassed the popularity of the original long ago. (pg. 645)

- Boltzmann machines act as a linear estimator for observed variables, but are typically more powerful for unobserved variables. (pg. 646)

- When initializing a deep Boltzmann machine (DBM) from a stack of restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs), it’s necessary to modify the parameters slightly. (pg. 648)

- Some kinds of DBMs may be trained without first training a set of RBMs. (pg. 648)

- Deep belief networks (DBNs) are rarely used today due to being outperformed by other algorithms, but are studied for their historical significance. (pg. 651)

- While deep belief networks are generative models, the weights from a trained DBN can be used to initialize the weights for a MLP for classification as an example of discriminative fine tuning. (pg .653)

- Deep Boltzmann machines have been applied to a variety of tasks, including document modeling. (pg. 654)

- Deep Boltzmann machines trained with a stochastic maximum likelihood often result in failure when initialized with random weights. The most popular way to overcome this is greedy layer-wise pre-training. Specifically, train each layer in isolation as an RBM, with the first layer on the input data and each subsequent layer as an RBM on samples from the previous layer’s RBM’s posterior distribution. (pg. 660)

- The DBM is then trained with PCD, which typically only makes small changes in the parameters and model performance. (pg. 661)

- There are modifications that can result in state-of-the-art results for a DBM. (pg. 662)

- Two ways to get around this procedure:

- Centered Deep Boltzmann Machine: Reparametrizing the model to make the Hessian of the cost function better conditioned at the beginning of the learning process. (pg. 664)

- These yield great samples, but the classification performance is not as good as an appropriately regularized MLP. (pg. 664)

- Multi Prediction Deep Boltzmann Machine: Uses an alternative training criterion that allows the use of the back-propagation algorithm which avoids problems with MCMC estimates of the gradient. (pg. 664)

- These have superior classification performance, but do not yield very good samples. (pg. 664)

- Centered Deep Boltzmann Machine: Reparametrizing the model to make the Hessian of the cost function better conditioned at the beginning of the learning process. (pg. 664)

- In the context of generative models, undirected graph models (DBM, DBN, RBM, etc.) have overshadowed directed graph models (Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Sigmoid Belief Networks, Variational Autoencoders, etc.) until roughly 2013 when directed graph models started showing promise. (pg. 682)

- While variational autoencoders (VAEs) are simple to implement, they often obtain excellent results, and are among the state-of-the-art for generative modeling, samples from VAEs training on images tend to be somewhat blurry, and the cause for this is not yet known. (pg. 688)

- Unlike Boltzmann machines, VAEs are easy to extend, and thus have several variants. (pg. 688)

- Non-convergence is a problem that causes GANS to underfit (one network reaches a local minima and the other reaches a local maxima), but the extent of this problem is not yet known. (pg. 691)

- For GANs, best results are typically obtained by re-formulating the generator to aim to increase the log-probability that a generator makes a mistake rather than decrease the log-probability that the generator makes the right prediction. (pg. 692)

- While GANs have an issue with stabilization, they typically perform very well with carefully a selected model architecture and hyperparameters. (pg. 693)

- One powerful variation of GANs, LAPGAN, start with a low-resolution image and add details to it. The output of this often fools humans. (pg. 693)

- In order to make sure the generator in a GAN doesn’t apply a zero probability to any point, add Gaussian noise to all images in the last layer. (pg. 693)

- Always use dropout in the discriminator of a GAN. Not doing so tends to yield poor results. (pg. 693)

- Visual samples from generative moment matching networks are disappointing, but can be improved by combining them with autoencoders. (pg. 694)

- When generating images, using the “transpose” of the convolution operator often yields more realistic images while using fewer parameters than using fully connected layers without parameter sharing. (pg. 695)

- Even though the assumptions for the “un-pooling” operation in convolutional generative networks are unrealistic, the samples generated by the model as a whole tend to be visually pleasing. (pg. 696)

- While there are several approaches to generating samples with generative models, MCMC sampling, ancestral sampling, or a mixture of the two are the most popular. (pg. 706)

- When comparing generative models, changes in preprocessing, even small and subtle ones, are completely unacceptable because it can change the distribution and fundamentally alters the task. (pg. 708)

- If evaluating a generative model by viewing the sample images, it is best to have this done by an experimental subject that doesn’t know the source of the samples. (pg. 708)

- Additionally, because a poor model can produce good looking samples, make sure the model isn’t just copying training images. (pg. 708)

- Check this with the nearest neighbor to images in the training set according to the Euclidean distance for some samples. (pg. 708)

- Additionally, because a poor model can produce good looking samples, make sure the model isn’t just copying training images. (pg. 708)

- A better way to evaluate samples from a generative model is to evaluate the log-likelihood that the model assigns to the test data if it is computationally feasible to do so. (pg. 709)

- This method is still not perfect and has pitfalls. For example, constants in simple images (e.g. blank backgrounds) will have a high likelihood. (pg. 709)

- There are many uses for generative models, so selecting the evaluation metric should depend on the intended use. (pg. 709)

- I.e. some generative models are better at assigning a high probability to the most realistic points, and others are better at rarely assigning high probabilities to unrealistic points. (pg. 709)

- Even when restricting metrics to the task it’s most suited for, all of the metrics currently in use have serious weaknesses. (pg. 709)